Conducting User Research with children

Children and young people are now a significant portion of the online audience, but performing research with this group is not without its unique challenges. Children have shorter attention spans and varying levels of understanding when compared to adults. They can respond unpredictably and require safeguarding or supervision, making them a tricky audience to work with when undertaking research.

Whether it’s your entire digital product or just an area of your website relevant to a young audience, you must be able to reach out to and engage with them. This guide will help you consider how to go about researching with a younger audience.

A brief introduction to user research with children

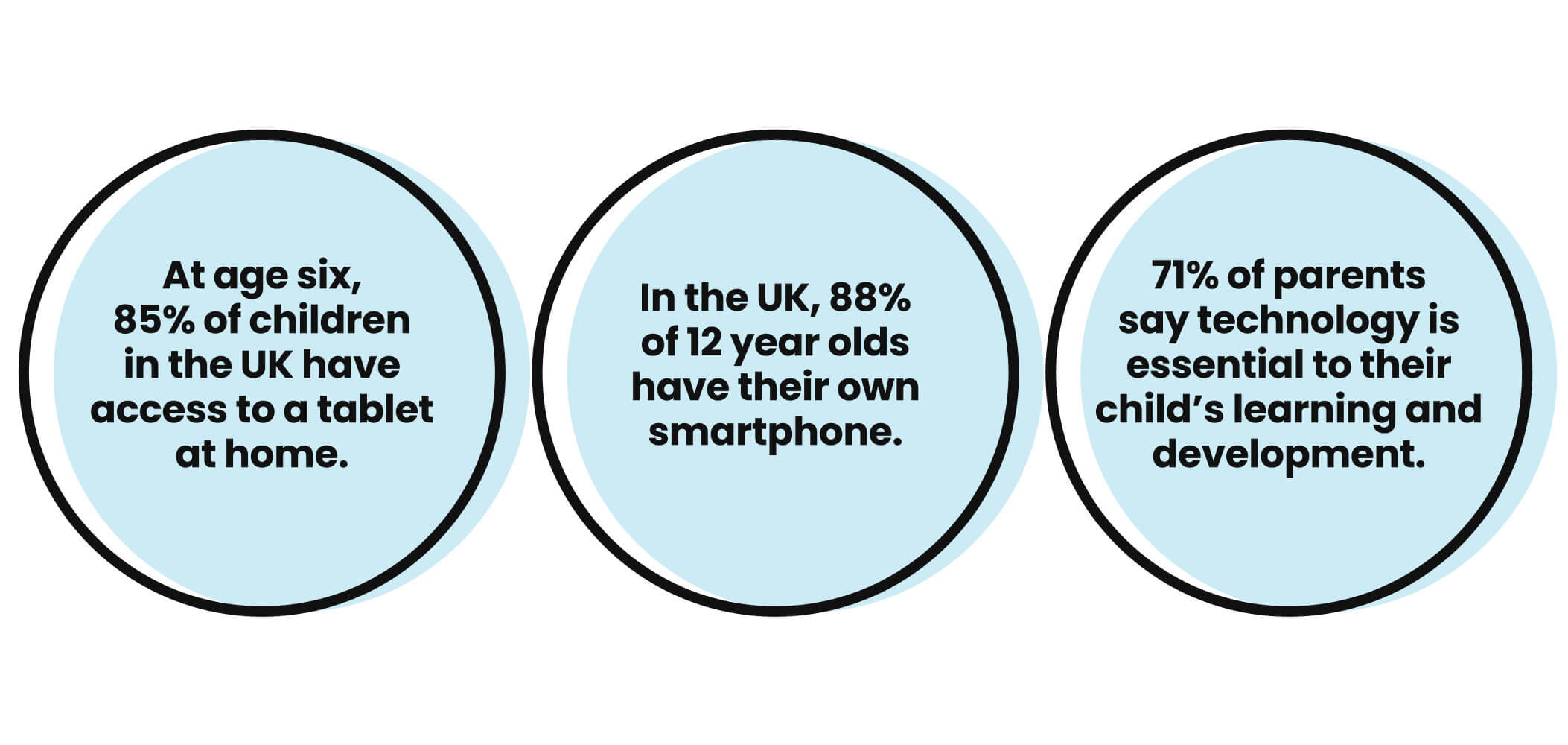

Children's technology usage is growing year on year in the UK:

- At age six, 85% of children have access to a tablet at home

- By age 12, 88% of children have a smartphone

- Almost 3 in 4 parents believe technology is essential to their child's learning and development.

Now more than ever, technology can bring huge benefits to children, such as the ability to play, develop knowledge, and bring family and friends together.

Therefore, conducting user research with a young audience is advantageous for forward-thinking brands and designing with them in mind is (naturally) more challenging but equally capable of providing exciting outcomes. If you have a product aimed at children, an engaging, rewarding user experience is key to its success, and user research is the foundation to achieve it.

User research is about learning directly from your target audience. It exists to understand user behaviours, needs, and motivations through observation techniques and other feedback methods. The insights from user research can inform your digital product's design, structure, strategy, and overall user experience, ensuring it truly satisfies your users.

We think undertaking user research is critical for young audiences since they're not just mini-adults – understanding their experience directly from them is invaluable.

Here are some of the fundamental reasons why you shouldn’t compromise on investment in user research:

- Develops a deeper understanding of children’s needs, motivations and the “why” of their behaviour

- Provides an essential foundation and the data to back up strategy and design decisions

- Decreases cost by reducing time spent developing digital products that aren’t engaging, user-friendly, or don’t solve your young user’s problem

- Helps eliminate internal bias, validates ideas, and resolves adult-opinion-based debates

The method of conducting user research depends on your product and objectives, the questions you are trying to answer and where you are in the discovery or design process. No two user research projects are identical (especially when children are involved!). We’ll cover this in more detail later.

There are decisive research methods that focus on putting the child at the centre, including observational studies in their own environment, interviews, and participatory design.

How can we define the group "children"?

Children today are digitally native and are the influencers of tomorrow - they see technology as a tool for expression, experimentation, and communication. But who are "children"?

"Children" in the UK are legally classed up to 18 years old. However, unlike the adult population, children change quickly; the difference in ability and maturity between a 5-year-old and a 10-year-old is vast. In contrast, there are very few (if any) differences in technical ability between 25 and 45-year-olds. Compared to adults, children have a very different way of understanding and processing the world around them and have varying levels of physical, mental, and social development.

A user experience that works perfectly well for most people most of the time might not work for children.

Children's needs are highly variable across several approximate age groups; each group has different behaviours and skill levels, and users get distinctly more tech-savvy as they age and develop.

Design for children relies on many other factors but typically falls into four age brackets:

- 3-5 years old – Low levels of understanding and perception. These children respond mainly to symbols and visuals and don't understand abstract concepts. They can use simple interactions on touchscreens.

- 6-8 years old – Children can think logically and have developed the ability to apply reason. Their reading and vocabulary skills are growing, and their understanding of complex statements is increasing. They can usually perform simple desktop interactions like mouse and keyboard use.

- 9-11 years old – Interactions are more advanced, and often by 11, children are physically interacting with technology like adults. They develop abstract thinking, can generalise, and begin to consider themselves individuals.

- 12+ years old – Children in this bracket can usually navigate the web successfully and find what they need. Although they are confident in their abilities, they're mainly distinct from adults in their impatience, lower reading skills, and inexperience with complex websites.

Like most adults, teenagers are adept at using technology independently and using logical thought, deductive reasoning and complex problem solving; age-specific research and design for this group relates to online safety. Therefore, the remainder of this guide focuses primarily on those under 12's.

- Of course, age isn't the only factor to consider when conducting research or designing. Still, it's relatable to demonstrate how important it is to choose and adapt research methods that fit with participants' cognitive, language, and motor skills.

Chat with our team about helping you with audience research

Key considerations for the younger audience and how to adapt your research

From the legalities of obtaining informed consent and ensuring the children's needs are always put first to the logistics of working with children and choosing the correct methodology, there's a lot to think about – we've pulled out some important considerations below to get you started.

Recruiting and setting up for younger participants

There are factors in the recruitment of younger audiences that are very different to recruiting for a similar adult-based study.

- The first is consent, which must always be taken extremely seriously, especially when researching with children

- You'll find guidance at reputable sources such as the NSPCC - you can always obtain legal advice if unsure.

- At a minimum, the child's parent or legal guardian needs to provide consent.

- Be mindful - while the child should have been informed of the research, they may not have explicitly chosen to participate in the study and may reflect that in their willingness to participate.

- Always ensure your participant is comfortable and aware that they can withdraw at any time.

Another difference is that your participant's attendance relies on at least two people – the child and the parent or caregiver. The chance of dropouts/cancellations is naturally higher, especially given the busy lives of parents and children.

We recommend recruiting more participants than you typically would. The set-up for children is also likely to need more thought; when running research in-person, ensure a separate waiting area with toys and entertainment for any surprise siblings or those who arrive early.

💡 Top Tip!

Money or gift cards are a typical incentive for parents, but it’s worth considering a small additional incentive to thank your younger participants. Keep children’s motivations appropriate (a bag of sweets may not please parents!), and always inform the parent of the incentive when seeking consent for your study.

Having the right attitude when researching with children

One of the most important things when working with children is to have the right attitude – the key to this is being flexible and patient. You must be prepared to change your ways of working as you go and to remain open-minded if a research activity is giving different results than what you had imagined.

Building rapport with children requires a friendly, non-judgemental attitude that doesn't come across as too authoritative – kind and calming language is a must.

Take extra care to reassure them in simple ways, such as making it very clear that they can get up to use the toilet anytime without needing to ask. Lessen any adult-child power dynamic by taking time at the start of a session to show interest in the things they love (and so are "experts"), making them comfortable and giving them a better sense of control.

💡 Top Tip!

Do a pilot session or two when speaking to a new group of participants. Though it seems obvious which research methods to use to test a particular design or feature, it’s worth running an early session to ensure you get the insight you need when performing research with children. Pilot sessions also allow you to trial your set-up, which can take time to prepare if it involves interactive games or drawing activities.

Selecting and adapting research methods

As with any audience group or project objective, choosing a suitable research method is essential to ensure we solve our problem and represent the needs of our users. For younger users, this is especially true as their understanding and reaction to different research methods can vary based on their cognitive, language and motor skills.

Young children may not always clearly express themselves using words; an interactive activity in their natural environment allows you to observe how they think and behave.

The research method must complement the audience, and for children, it may even need adapting slightly for each child to get the most out of the session. Older children and teens are (often) highly influenced by their peers, so holding focus groups with them could potentially lead to biased results. In contrast, younger children may find friendship pairs encouraging.

💡 Top Tip!

Ensure that any tasks you choose are relevant and age-appropriate. For example, a 7-year-old may not realistically be signing up to create an account so asking them to evaluate a sign-up form is unsuitable. However, once an account exists, they may enjoy personalising their avatar and changing the way your app looks for them.

Determine the role of the parent or caregiver

Parents are the expert when it comes to their children! This influence can mean that they can help encourage responses, remind children of their experiences, and help to "translate" answers if you are unsure what the child is trying to say. However, you may also find that some well-intentioned parents interrupt, re-phrase your questions in a leading way, or take over "explaining" the child's idea. You can question whether the parent needs to be 'in the room'. If they remain in the room, determine roles up front to avoid parents needing to take control of the research session.

💡 Top Tip!

The parent/caregiver may want to be present when conducting a session remotely online. Set expectations before the session by letting them know that they can prompt their child to answer, so long as they don’t drive responses before the child has had a chance to reply. Ensure you also take time to ask for the parents’ insights and opinions when it is appropriate.

Five insights from our research with children

The audience for your website may not span from 3-year-olds to teens, especially considering the very different design needs between younger children and older children, but that's not to say there aren't universal insights that can get you started on any digital product for children. Here we share five of our top picks.

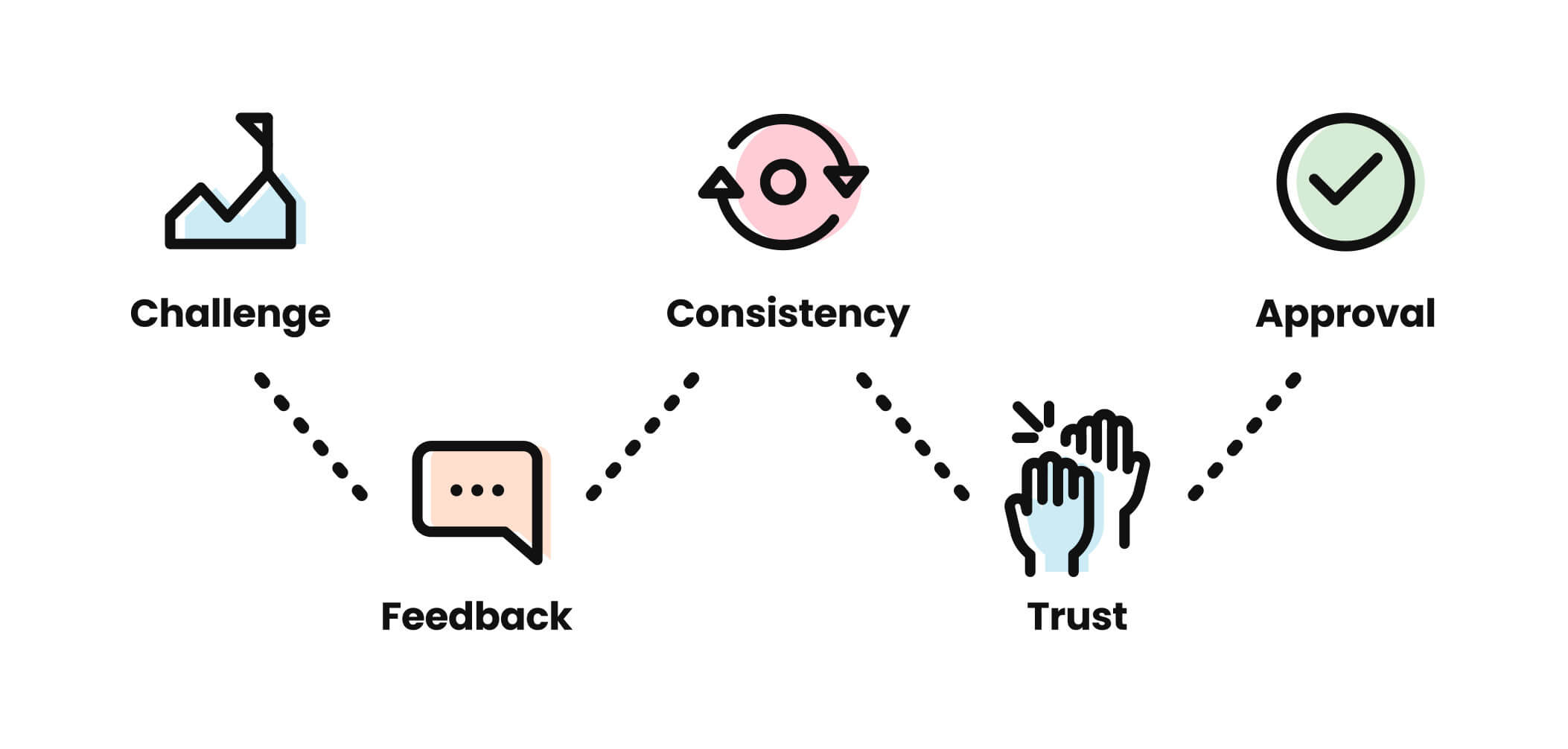

- Children love a challenge – While there are many (basic) functional activities (think banking, reading emails etc.) that adults appreciate being seamless, children want technology to be challenging and fun.

- Well-designed activities that are enjoyable to learn lead to an app or website that children enjoy – you may hear the term "babyish" from a child who doesn't find something challenging or engaging enough.

- For kids' games, this philosophy creates multiple steps with small in-game rewards at each step that make the accomplishment more significant in the end.

- Instant feedback – Kids benefit from learning how to use things independently but struggle to concentrate for extended periods.

- While adult users can wait for something to happen, children need instant gratification when interacting; UX researchers should constantly speak to children giving them feedback for every interaction and keeping them engaged.

- This behaviour differs subtly from adults, who only require feedback as confirmation or when they do something wrong.

- Consistency and clarity – It is a myth that digital products must have garish, flashing features to grab their young audience's attention. Too many conflicting design elements make it unclear to them which ones they can interact with.

- Cheerful and relatable graphics are important, but unnecessary elements such as overcrowding and flashing images may confuse children.

- It's also essential to use icons that have an obvious meaning that kids can easily understand – children under 9 tend to be literal thinkers, so they may think a hamburger menu icon refers to a hamburger!

- Kids are trusting – Unlike adults, children don't reliably predict or understand the consequences of their actions ahead of time and are typically much more trusting than adults.

- Most knowledgeable product designers and managers understand how to create addictive experiences which drive engagement and revenue.

- However, many of these are unacceptable when designing for kids.

- You are responsible for building safeguards into digital products for children – avoid design patterns or features intended to be addictive or increase screen time with no educational benefit to kids.

- Parental approval – while your design must be child-centred, design for children is still paid for by parents, so always consider them.

- It's no surprise that when we've asked what our child participants might do if they wanted to buy [a product], the most popular response is "please, mum?!?".

- In addition to purchasing power, parents can refuse or take away products they consider unsuitable.

- Have an area (on the website/app) that provides parents security about the organisation, the product goals and what the child will come away with while reassuring them that their child will be safe.

So how could getting children engaged improve your business?

Many companies (for example, Amazon and The Entertainer) are missing out on opportunities to provide a creative and stimulating environment that children identify with and want to use. By establishing areas of their websites that speak individually to children and adults, businesses can create brand awareness early on and engage with children and their parents.

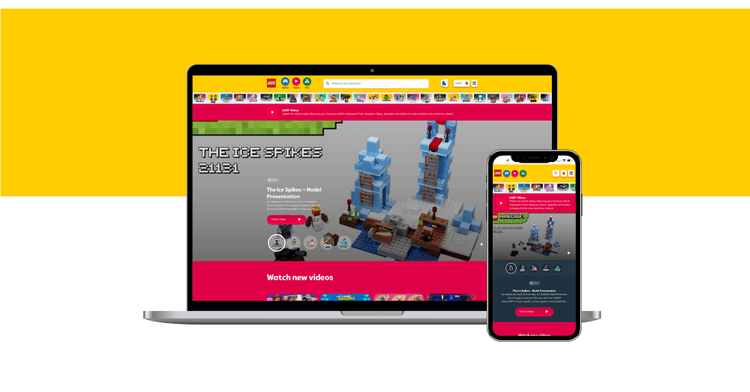

Lego.com is a prime example: while the primary area of the website is dedicated to the sale of Lego products and aimed at adult shoppers (AFOL), the mini brick giant has an incredible "play zone" for children. This content-rich area includes interactive games and learning activities across many play-set themes. The zone also contains appealing descriptions and videos of their brick sets. This area motivates and stimulates children to build with Lego in the virtual world while encouraging them to play with Lego offline in the real world.

And it doesn’t all have to be about retail: one example is Tate galleries, which aim to encourage children to be inspired by art. Tate has a kids section on their website where children can play games and quizzes, watch videos about art and submit their creations. By making their brand fun and familiar to kids, they are expanding their audience and attracting a new demographic to (what is) a traditionally adult activity - visiting an art museum.

By providing children with a safe and inspiring environment, you can find lifelong advocates for your organisation, for children and parents alike.

In summary

Nowadays, children spend more time online than ever and use technology confidently from an early age, creating a niche for digital products for children. While this means designing children’s apps can reap monetary rewards, it also (and perhaps most importantly) means designers and content creators have the potential to influence an entire generation.

These elements create the demand for good child-centred design, which is more than just flashing colours and silly sounds.

First and foremost, user experience for kids should be based on children’s psychology and rely on solid user research. When researching with children, tailor your approach and activities to the cognitive, physical, and technical skills of the group you’re designing for - the insights you’ll gain will be invaluable to your business.

Loading

Talk to us about learning about your audience

Tell us your needs and we'll be in touch

Recent audience and user work

Do you have a challenge we can help with?

Let's have a chat about it! Call us on 01903 337 580