How to Sell Insurance to Irrational Customers

By Stephen Courtney|19 Aug 2021

Conversion services | 13 MIN READ

Insurers treat their customers like perfectly rational economists who want to limit financial risk at the lowest possible cost. That approach has created a race-to-the-bottom, lowering premiums at the expense of consumer trust. To survive the disruption of the digital era, traditional insurers must rethink their products for human customers and learn what really makes us buy insurance.

That consumer behaviour is irrational should not surprise anyone. To appeal to people with human brains, insurers need to treat them like customers, not calculators, and offer them something worth buying.

Dr Stephen Courtney, CRO and UX specialist

In May 2016, Howard Kunreuther (Professor of Decision Sciences at the University of Pennsylvania) delivered a presentation to the Federal Advisory Committee on Insurance. Ten years after Hurricane Katrina and five years after Hurricane Sandy (together, responsible for over $150 billion of damage), the Committee had a problem: high-risk homeowners were cancelling their insurance.

Not only was the situation puzzling, but it seemed to follow a pattern. In Northridge, California, where a 1994 earthquake had caused over $13 billion of damage, insurance rates had fallen to just 10%. Before the floods that struck northern Vermont a few years later, just 16% of the 1,549 flooded households were covered. Drawing on experience from a career in behavioural research, Kunreuther’s explanation was simple: people make irrational choices about insurance.

Hurricane Sandy, 22 October 2012 – 2 November 2012

Hurricane Sandy, 22 October 2012 – 2 November 2012

Kunreuther showed how decision-making biases cause people to under-insure themselves against disasters. To rectify this, policy makers needed to dissect those decisions and decode the rule-of-thumb assumptions (“heuristics”) that shape everyday choices. Whilst this is a helpful insight for politicians, human decision making is an even more pressing concern for the marketing teams whose job is to sell insurance. Understanding what makes someone purchase a policy is a necessary correction for an industry in crisis.

How to Sell Insurance to Imperfect Customers

Broken into four sections, we'll take you through:

- A Dangerous Time For Insurance

- Why Insurance Does Not Add Up

- What Makes Us Buy Insurance

- Don’t Wait for Disruption

A Dangerous Time for Insurance

Trust in insurance companies is at an historic low. A 2021 YouGov survey found 68% of people believe that: “insurance providers will do everything they can to avoid paying out for a legitimate claim.” Worryingly, this mistrust is most acute in younger customers. According to a survey by Insurance Times, only 37% of 16-29 year olds believe that an insurance company would honour a legitimate claim.

Insurers have the same mistrust for their customers. According to the Association of British Insurers, companies spend over £200 million a year to detect fraud. This outlay increases the “Load” that they must add to premiums, whilst natural cynicism reduces the amount consumers are willing to spend on a policy.

Despite these shrinking margins, insurers are forced to invest more and more to find new customers due to competition from comparison websites and high levels of customer “infidelity”. Of those with an active insurance policy, 73% are actively looking for an alternative. This lack of brand loyalty has led analysts to label insurance as the digital industry most vulnerable to disruption.

When policies are sold like investments, customers struggle to tell them apart. Presented with identical options, they will simply choose the cheapest one. On top of that, most policies include clauses that invalidate their cover, and few provide any value until the holder makes a claim. That means customers never experience peace of mind and, after a short period without a claim, will come to the obvious conclusion: insurance is a bad investment.

To survive, insurers must redesign their products and rethink how they communicate. Rather than leaving actuaries to create policies and comparison sites to sell them, product managers and marketers must help to design new types of cover that customers want and appreciate. The first step towards building a customer-friendly alternative is realising that insurance is not a sum.

Why Insurance Does Not Add Up

When visitors land on an insurer’s product page, they are greeted with a deluge of cover limits, policy maximums and payment choices. They then need to choose an excess amount and select from a menagerie of exotic-sounding add-ons. Insurers assume that their customers will weigh their risks against the premiums. In reality, most people do not go shopping with a calculator.

Kunreuther’s analysis showed how some people avoid painstaking cost-benefit calculations. When the probability of a disaster falls below a threshold, it is simply treated as 0%. However, the Threshold Effect is only one example of how bias shapes insurance choices. In his best-selling book, Nudge, Richard Thaler noted that recent experiences (even those of a close acquaintance) would influence and change buying behaviour:

This type of decision-making is not unusual; psychologists and behavioural researchers have shown that most of our day-to-day choices use imperfect logic, heuristics and simple bias. Even so, there are few areas with more documented evidence of irrationality than insurance…

1. The Preference for Insuring Small, Probable Losses (1977)

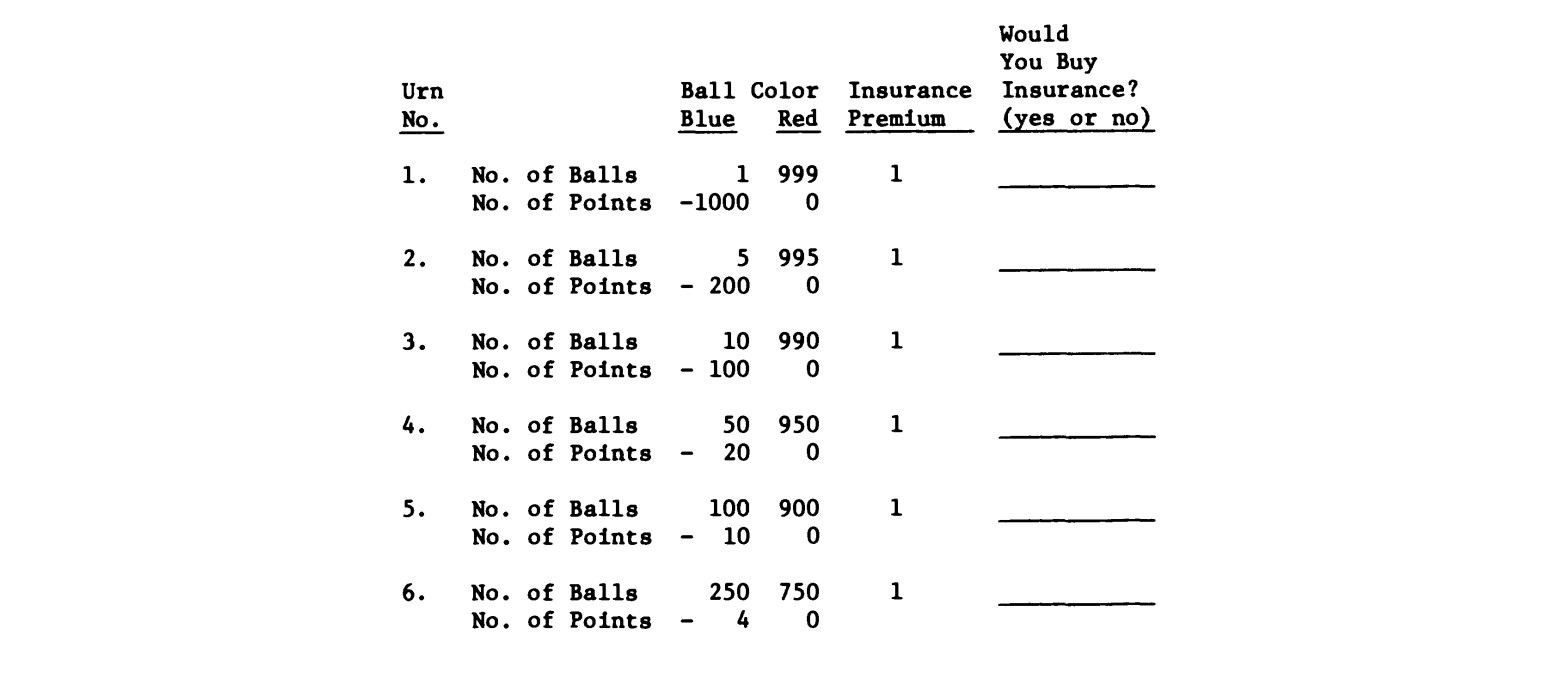

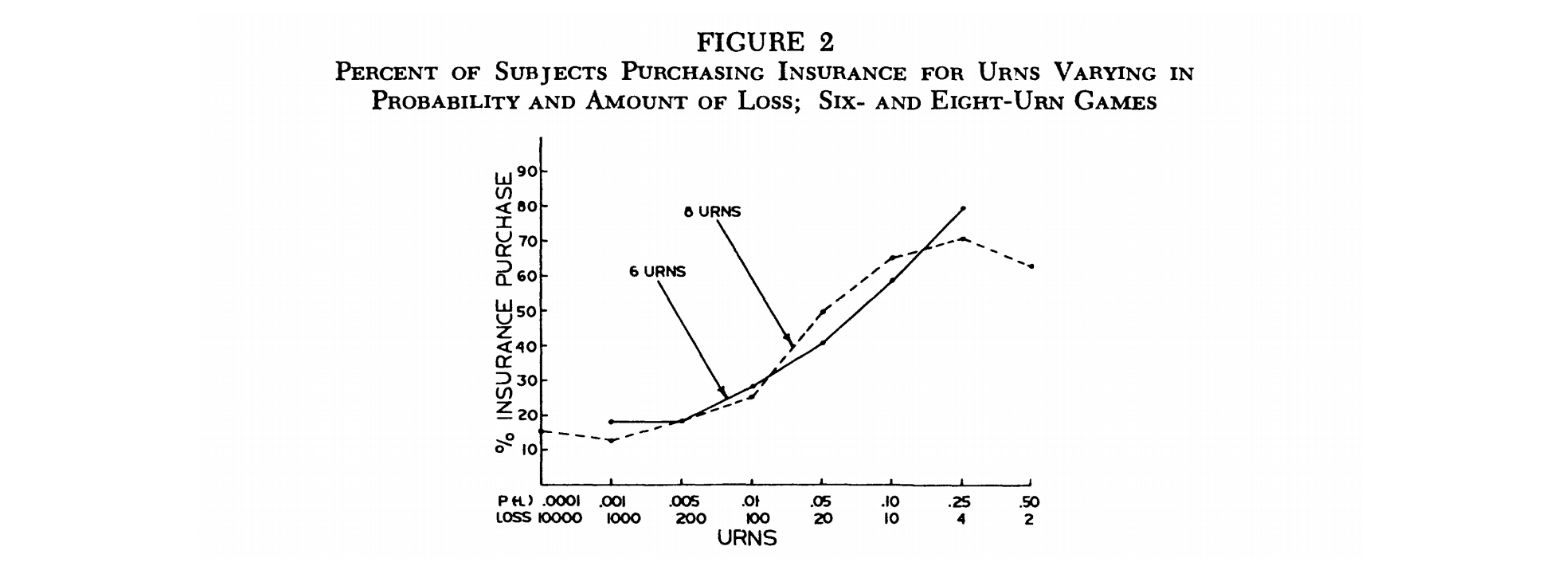

A team of researchers from the University of Pennsylvania were the first to demonstrate the Threshold Effect using simple gambling games. Participants chose a ball at random from a series of urns, knowing that a blue ball would cost them points. Each urn displayed the odds of picking a blue and, to make each one equally risky, a blue cost more when the chance of picking one was low. The participants could “insure” any urn for a fixed price, and the aim was to finish with as many points as possible.

Remarkably, the players’ strategies almost perfectly imitated the insurance choices of real-world consumers. Even though the urns had an equal risk value, participants chose to insure probable, moderate risks far more often than improbable, large risks.

2. The “Availability” Bias (1974)

Instead of calculating the probability of an event, most people judge it based on how easily they can call examples to mind (an effect called "Availability"). In 1974, the economist's Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky demonstrated the effect by challenging participants to guess which of two groups were more numerous:

- Words that start with "R"

- Words that have "R" as the third letter

Most participants chose the first group because it is easier to think of words with a first letter. However, with a small amount of deduction, it becomes clear that the second group has many more cases (including the word: "word").

Richard Thaler's observation that recent memory drives insurance choices occurs (partly) because consumers judge probability based on availability. The effect is evident when comparing the rate of policy take-up before and after a flood.

3. Framing Effects (1981)

Having demonstrated the principle of Availability in their Judgement Under Uncertainty, Tversky and Kahneman produced another study that showed how simply rewording options could persuade seemingly rational people to alter, and even reverse, their preferences. This framing effect was particularly powerful when applied to questions about risks, gambles, and insurance.

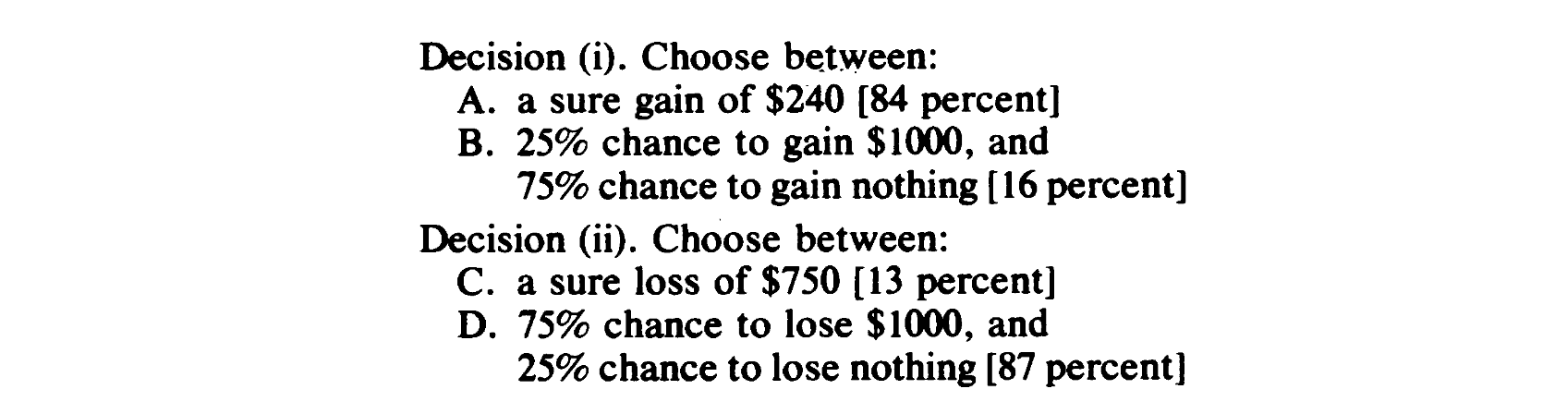

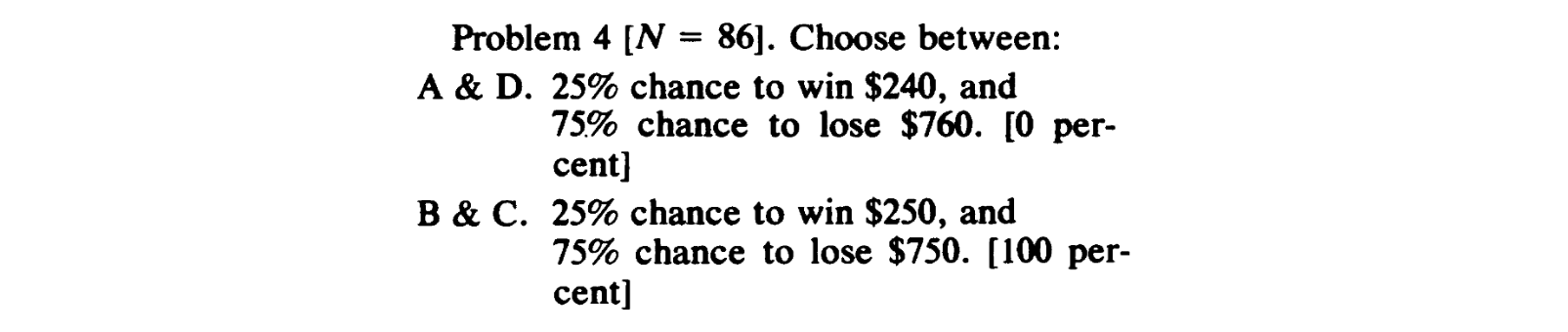

“Problem 3” in The Framing of Decisions and the Psychology of Choice

For example, given “Problem 3”, 73% of Kahneman and Tversky’s participants opted for a combination of A for Decision 1 and D for Decision 2. When the decision was a positive gamble, they were “risk-averse” (sacrificing a better deal for a certain outcome), whereas a potential loss prompted “risk-seeking” choices.

More surprising than an irrational choice being the most popular is the reversal of participants’ preferences by presenting the options differently. Combining Decision 1 and Decision 2, 0% of participants chose A & D.

By experimenting with framing, Kahneman and Tversky found consistent biases that have nothing to do with mathematical probability:

- People will pay twice as much to reduce risk from 1% to 0% as they would cutting 2% to 1%.

- A vaccine that works against all strains of a virus 50% of the time is valued less than a jab that gives full protection against 1 out of 2 (equally dangerous) strains.

- “Probabilistic insurance” (which pays out 90% of the time) is less valuable than “Conditional insurance” (which pays out in 9/10 situations).

Seeing how susceptible their subjects were to irrational biases, the results forced Kahneman and Tversky (both professional economists) to make an uncomfortable observation - consumers rarely buy insurance for purely financial reasons.

It appears that insurance is bought as protection against worry, not only against risk.³

Given that artificial thresholds, flawed intuition, and framing determine consumers’ insurance choices - designing and marketing policies in purely mathematical terms does not add up. With that in mind, the next step towards a customer-friendly alternative is understanding how consumers think about insurance.

That consumer behaviour is irrational should not surprise anyone. To appeal to people, insurers need to treat them like customers, not calculators, and offer them something worth buying.

Talk to us about your conversion optimisation challenges

What makes us buy insurance?

Insurance is many things: protection from worry, a performance of identity, even superstition (equivalent to a sports fan betting against their team). People are more likely to insure a better-looking car and are even more likely to claim for something they feel attached to.

Understanding what motivates someone to buy insurance should be the priority for anyone designing a policy and the first step for anyone trying to sell it.

Insurance as a fear of flying

If you had taken a flight from New York to Chicago in 1960, you would have encountered an unusual offer in the airport lounge. The early years of air travel saw a boom in “flight insurance” sold through vending machines and clerks. For as little as $0.50, travellers could purchase a policy that would payout in the event of a crash. Anxious travellers could buy up to $62,500 worth of cover, and over half of customers bought the total amount.

At such a low one-off cost, the popularity of flight insurance seems unremarkable. That is, you compare it with the far cheaper and more comprehensive cover offered by ordinary life insurance. During a famous legal case in 1963, it was reported that a group of underwriters had sold $84,564,025,000 worth of insurance and paid out only $1,388,839 in claims. Eventually, travellers became wise to this actuarial sleight-of-hand, but the brief boom demonstrates something important about what makes people buy insurance.

Purchasing a policy helps to resolve specific and highly tangible anxieties. The thought of a plane crash affects people in a way that statistical risk does not, and similar fears (concrete, emotive, and narrative) play a disproportionate role in many of our day-to-day choices. For example, despite the relative safety of nuclear power, public anxiety has remained acute since the high-profile disasters of the 1980s. Compared to the imagery of contamination, the more pressing threat of environmental change seems immaterial.

Understanding how anxiety is contained within specific, concrete ideas is not an invitation for insurers to manipulate their customers. Instead, it should remind product designers and marketing teams that they can provide a better service and communicate more clearly if they think about risk like a customer rather than an actuary. Identifying and resolving customers’ fears with a genuinely reassuring product is the best way to address the “infidelity” that affects insurance brands.

Insurance as a sign of affection

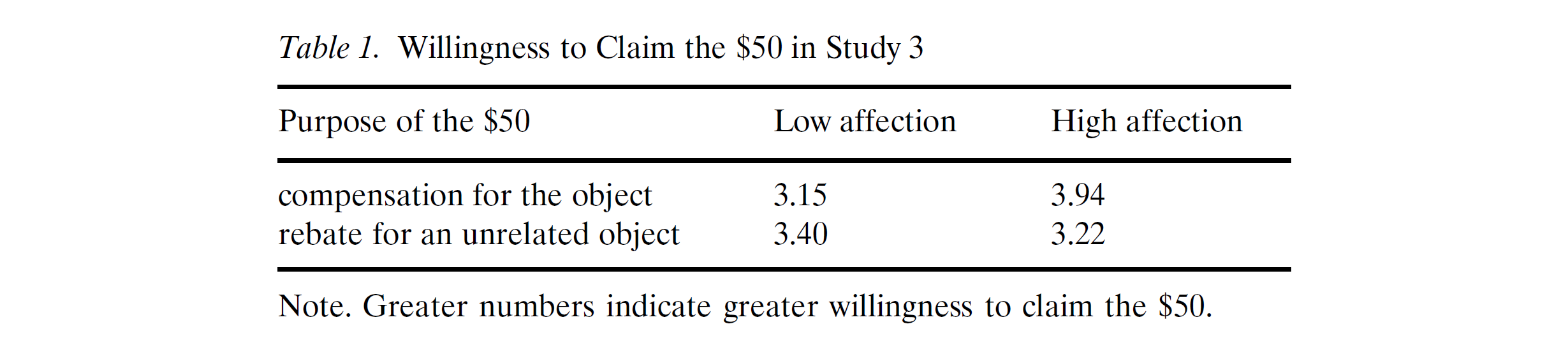

Imagine that you have paid to ship two (equally valuable) paintings home from a honeymoon. They were sold together, but one of them reminds you of a special location whilst the other has no sentimental value. If the courier offered you separate insurance on each painting, which would you pay to insure?

In economic terms, the item covered by an insurance policy is irrelevant. Nevertheless, researchers have shown that even a hypothetical attachment can change whether someone chooses to insure something. A recent study conducted at the universities of Pennsylvania and Chicago found that participants would be willing to spend over twice as much to insure an antique clock if it came with an emotional backstory. Participants were also willing to go to more extraordinary lengths to claim an insurance payout for an item they cared about.

Not only are people more likely to insure something they care about, but attachment changes how they think about the cover. The fact that people will go to greater lengths to make a claim when they have lost something meaningful suggests that insurance provides emotional, not just financial, compensation. Rather than behaving in the way that economic analysis suggests they should, consumers’ insurance choices change dramatically depending on what they're insuring.

Insurance plays a subtle role in the psychological and emotional lives of policyholders. At the same time, consumers make choices that are unexplainable in purely economic terms. Because of that, marketing teams and product designers must pay close attention to the particular motivations of their audiences, building policies and brands for real, human customers.

Behavioural research shows that insurance decisions rarely add up and that customer's motivations are far more complicated than simple economics. However, as well as correcting the idea that consumers are perfectly rational, this same research can also help insurers design more appealing products. Behavioural scientists and economists demonstrate new ways to appeal to human customers.

How to Build Insurance for Humans

Having adopted a more human view of their customers, insurers still face the challenge of creating irresistible products. Here, too, they can be guided by the quirks and biases of irrational consumers. Whilst behavioural science does not provide an instruction manual, it does point to areas of the customer experience where hidden value can be unlocked. Insurers can draw from over 30 years of research highlighting a few key concepts…

1. The Problem of Trust

Classic behavioural experiments such as The Prisoners Dilemma have shown how fragile trust can be, even when cooperation is in everyone’s interest. Insurance, by contrast, is an adversarial relationship; in the event of a claim, customers cost insurers money. So, in 2016, a company called Lemonade (which included the Behavioural Economist Dan Ariely on its board) looked for ways to remove conflicts of interest from insurance.

Lemonade takes a flat fee at the point of transaction. After that, any premiums that have not been paid back in claims are donated to the customers’ nominated charities. Policyholders know that Lemonade gains nothing by refusing a claim, and they also know that fraudulent claims take money from their favourite charity. The result? Not only did Lemonade earn over $2.9 million in gross written premium within its first year of operations, but it also received an unprecedented amount of returned pay-outs from wrongly compensated customers.

2. Mental Accounting and Non-Fungibility

In one of his “Anomalies” articles, Richard Thaler identified a strange quirk in the way households save and spend money. Whilst economists assume that all types of wealth are equivalent (an assumption called “fungibility”), real families deal with pensions, savings, property and income according to very different rules.

A simple way of thinking about how people actually behave with respect to various types of wealth is to assume households have a system of mental accounts.4

Mental accounting explains why conventional policies have such a stubborn value ceiling: once someone has budgeted for standard home insurance, it is difficult to sell them a more expensive policy.

So, insurers should focus on differentiating their products rather than increasing average spend through add-ons (which will often reduce conversions so much that it defeats the purpose). An offer distinctive enough to occupy a new category within the customer's mental accounts would be able to command a more realistic price.

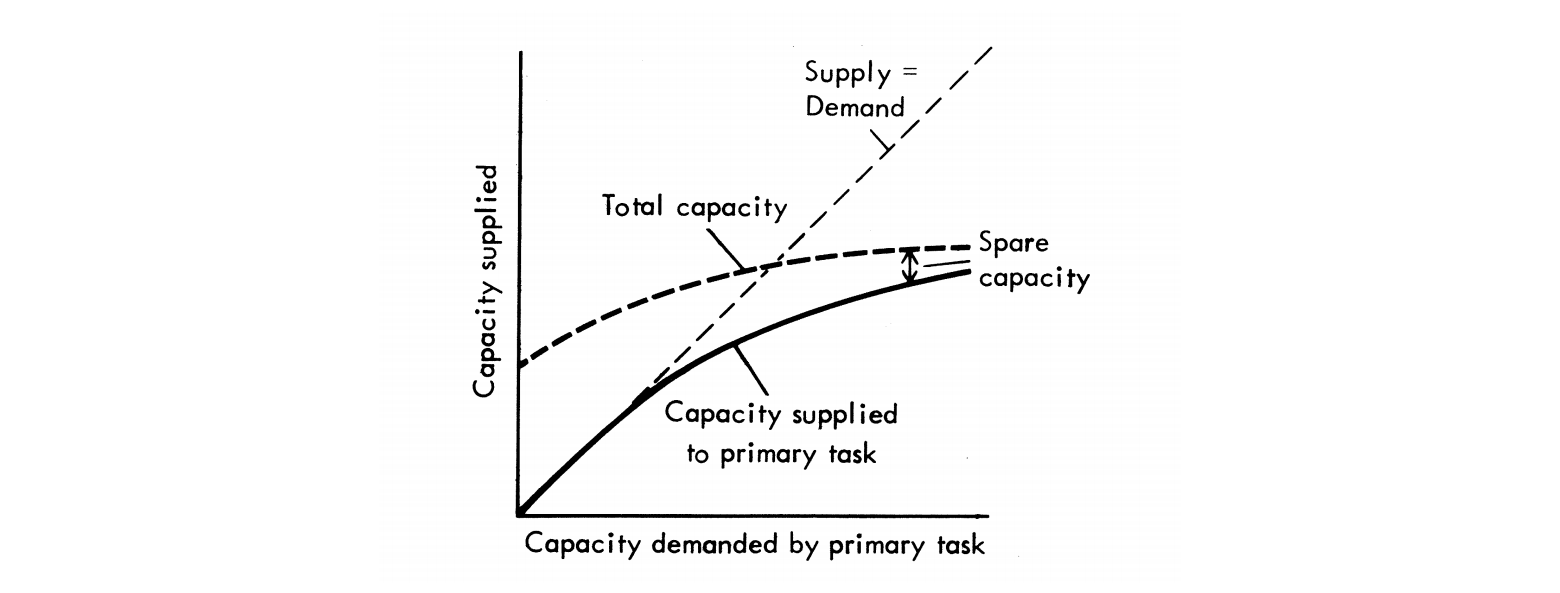

3. Cognitive Load and Limits of Attention

Insurance is a grudge purchase for most people, an obligation to be suffered whilst expending as little effort as possible. In their Attention and Effort, Kahneman and Tversky show how much effort goes into careful thought (and how far most people will go to avoid it). With that in mind, insurers should work hard to make their policies as intuitive and straightforward as possible.

Figure 2.1 in Attention and Effort

One way to reduce Cognitive Load for reluctant customers is to simplify complex pricing packages into a series of tiered plans (the standard format for SaaS products). Presenting options in parallel allows customers to “isolate” the features they want without wading through a marathon of confusing upsells. Tiered pricing would make it easier to test products and features, whilst the naming and presentation of different tiers would help make cover options more concrete.

4. Myopic Loss Aversion

Another of Thaler’s “Anomalies” relates to what is known as the “Equity Premium Puzzle”. Whilst stocks are risky in the short term; portfolios generally pay off over long periods. That means stocks are disproportionately cheap when compared to fixed investments (such as government bonds). It also means that Wall Street brokers pay far too much to avoid risk.

To explain this, Thaler combined two concepts: Myopia (how people undervalue long-term factors) and Loss Aversion (how people feel losses more intensely than gains). Because brokers monitor their investments and pay more attention to occasional losses than overall gains, it costs them more to bet on stocks than it does to play safe.

Unfortunately for insurers, customers also evaluate policies regularly. Like brokers, they will be painfully aware that their premiums (assuming they haven’t claimed) earn them nothing. So, to stem the annual tide of cancellations, insurers must find ways to reframe policies as a service rather than an investment.

Whilst these insights offer part of the solution for insurers, they must be accompanied by comprehensive changes in the delivery and branding of products. In the same way that Starbucks found hidden value by repackaging coffee as a branded experience, the industry's next big disruptor will have to transform insurance itself. To achieve that kind of grass-roots reinvention, insurers will have to break open the siloes that separate actuaries, marketing teams and customer support.

Don’t Wait for Disruption

As Kunreuther showed in his presentation to the FACI, behavioural science provides a much-needed correction to an industry built for perfectly rational customers. Whilst it doesn’t offer hard-and-fast rules or allow marketers to predict consumer behaviour, it points to aspects of the customer experience that traditional insurers have neglected. That creates a new problem: how can insurance brands try new approaches without losing their place at the table?

The most successful digital era businesses have found ways to innovate without suffering the financial and reputational hit from occasional dead-ends. Conversion rate optimisation, a test-and-learn process built on A/B testing and user research, has allowed brands like Amazon to innovate new services with extraordinary precision. The same approach has enabled Netflix to optimise new features and algorithms whilst Booking.com has achieved unprecedented conversion rates with highly persuasive user experiences.

Insurers can develop their own competitive advantages in the same way, using live tests to build products and marketing content around real humans. And, as the leading CRO agency for financial services and insurance brands, we have developed optimal processes for A/B testing insurance websites. To learn more about our work with insurance brands, or to discuss a disruptive insurance project, contact our CRO team and set up a strategy call.

Five ways to supercharge your insurance A/B testing program

Read this great blog written specifically for anyone working in the insurance sector looking to supercharge and positively impact A/B testing programs.

- ¹Howard Kunreuther, “Reauthorizing the National Flood Insurance Program”, Issues in Science and Technology 34 (2018), 45. (Find the full article here).;

- ²Richard Thaler, Nudge: Improving Decisions about Health Wealth and Happiness (Boston, 2008)

- ³Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman, “The Framing of Decisions and the Psychology of Choice” Science 211 (1981), 453-458.

- 4Richard Thaler, “Saving, Fungibility and Mental Accounts”, Journal of Economic Perspectives 4 (1990), 193-205.